What Does Economics Say About Lateral Entry in the IAS?

Conventionally, the role of private businesses has been limited to profit-making. Now, the role is expanding to include other aspects, such as having a positive impact on society, employees and the environment. In other words, companies earlier were providers of private goods, but are now moving towards providing public goods, too.

There are strong similarities between the changing roles and ideas of companies and that of the structure of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) from a pure “private good” to a “public good” (includes service).

Let us start by understanding the nature of public and private goods.

Typically, two well-known properties of goods are called non-rivalness and non-exclusiveness. Nonrival goods can be shared easily and perhaps even without cost. Examples could be an empty highway, an empty park, or housing that maintains certain standards for all the people living there. Once the good or service is available to any one person, the same amount (or nearly so) is also available to all others.

An often-related but distinct problem refers to goods that you cannot keep people from gaining access to or use of; these are called non-excludable. This means that you cannot prevent anyone from consuming that good. An example would be clean air, or the benefits of living in a city with low air pollution levels. Once you’ve cleaned up the air, everyone nearby has access.

However, some nonrival goods are excludable. The technical term for these is club goods: they are both shared and restricted, like a Club open to members. You can put a fence around a pool or a golf course, or require some criteria for eligibility, and so on.

Some nonexcludable goods are rival, which are sometimes called commons goods. As in the famous “problem of the commons,” these can be used up, but are often open to many. Even free parks or wide-open pastures can eventually get crowded.

Now let us connect the similarities of these goods to the IAS.

There are two unique features of the IAS. First, there are two routes to enter the IAS (and become eligible to write IAS after their names) - direct route through a nation-wide competitive examination and promotion from the state services. This entry restriction makes the IAS a club good, which can be shared, subject to certain requirements. Second, the idea of excludability is akin to reserving some positions for the IAS, only. The technical term used is encadrement of such positions.

Having established this correspondence, let us see what has happened during the last 75 years.

The progenitor of the IAS was the Indian civil Service (ICS). The entry barriers were formidable. Recruitment was originally restricted to the British and examinations were held only in England. Once in the civil service, removal was near-impossible and higher-level posts were earmarked only for the ICS (includes IAS). Even though the entrance examination was open to all (with some qualifications), access to positions in the States and the Central Secretariat was restricted to the ICS only. In this way the ICS (and its successor IAS) was a private good.

The IAS was opened to state civil services and occasionally to the military personnel, and this nonrival property made the IAS acquire some features of a club good; not available to ‘outsiders’ with access limited to only those selected through an entrance examination, or promoted from the state civil services.

Over time, the IAS did acquire some properties of nonexclusiveness. Higher positions in the Central Secretariat were opened to specialists in areas such as finance and commerce. These were one-off events and not made part of the system. Only now has this changed with the appointment of other central services to higher-level positions in the Central Government.

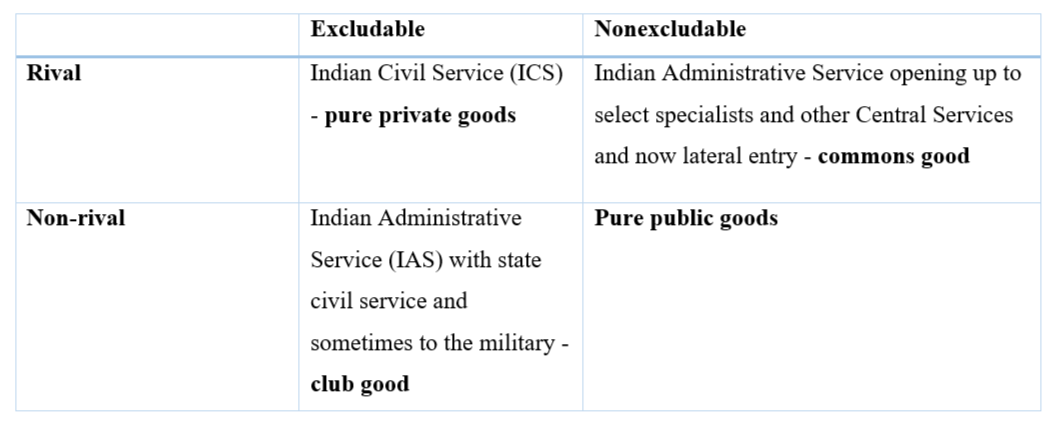

In this way, the IAS acquired some characteristics of common good where entry is restricted, but appointment to some positions is opened to a few other services. These ideas are depicted in the table below:

As the table shows, lateral entry means opening up positions at various levels in the Secretariat to "outsiders". This is the natural progression to morph the IAS into a nonexclusive good with more and more characteristics of a commons good.

Converting the civil service into a commons good will continue in both de-jure and de-facto ways. Opening up of top positions in the central secretariat or DG posts in the paramilitary forces for cadre officers are examples of de-jure changes. De-facto, on the other hand, means engaging more consultants, advisors and external agents/entities do the actual work.

As de-jure takes time and often faces resistance, transformations will take a de-facto route, at least in the short run.