Bharat Future City: An Indian Way of Doing Regional Development

Key takeaways:

Telangana has decided to build a fourth city, called the Bharat Future City. Post-1991, increasingly the spatial structure of Indian cities is market-driven. As a result, suburban characteristics are being superimposed on the periurban regions surrounding urban areas. This amalgamated spatial structure is best described as a periburb (periurban + suburb).

The Bharat Future City is one such periburb region.

Around 15 years ago an India-centric regional plan was prepared for the third and fourth cities of Hyderabad. This article is a concrete account of the practice of regional planning then and provides some guidance to the way forward for the Future city.

During colonial rule, Indian cities were developed primarily to service an external “metropole” and grew in the form of a dendritic market system. Even after independence, governments paid little attention to urban planning and city development. However, globalization during the 1990s increased the integration of the national economies with the global systems of production, consumption and distribution; moreover, technological advances in transport, communication, and computer technology have led to space-time contraction.

Because cities are the primary spatial framework within which capital, goods, people and information are concentrated, urban space formation is rapidly being shaped by globalization. Cities south of Vindhyas[1], were better situated to benefit from the effects of globalization because of initial advantages: contain critical mass of forward-looking technology promoters, availability of land pools, entrepreneurial state governments, availability of technology graduates, and better physical infrastructure and amenities.

The dendritic hierarchy was characterized by a high ratio of villages to cities and an imbalanced hierarchy of settlements. Post-independence; therefore, governments focused on village development, ignoring “urban identity” as a separate domain.

Cities continued to grow unattended due to agglomeration linkages, especially the presidency towns, state capitals and cities in which industries were set up to perform the role of growth poles. Increased economic activity in major urban centres was also accompanied by in-migration and an accentuation of existing gaps in the central-place hierarchy.

Integrated Development of Small and Medium Towns (IDSMT)

The role of cities as drivers of economic development and their special needs was only realized in 1979, when the Government of India formulated the Integrated Development of Small and Medium Towns (IDSMT) scheme to reduce migration to the large cities through the development of small and medium towns. This was expected to reduce imbalances in the central-place hierarchy as well.

Rise of parastatals

Structurally, the minimalist agenda entrusted urban functions to verticals, such as parastatals that were specifically tasked to do regulatory urban planning, build houses and construct and maintain utilities. Superimposing verticals on the existing urban governance templates led to the Delhi, Mumbai and the Kolkata governance models, given in Box 1. Moreover, reliance on vertical parastatals generated conflicts with the urban local bodies, leading to fragmentation and overlap of functions.

Starting in the early 1990s, the Government of India sought to address the democracy deficit by approving the 74th Constitutional Amendment and later implementing the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM) reforms agenda. Independent commissions, such as the II Administrative Reforms Commission and the 13th Finance Commission also recognized the importance of bringing about urban reforms to prepare prospective mega cities to govern better.

[1] Mountains in Central India

Conventionally, periurban areas were located on the city boundaries and were a landing ground for rural residents migrating to cities. Congestion, multiple interactions among strangers, short streets, and mixed land uses define the periruban space. Now, well-known suburban characteristics are being superimposed on the periurban and increasingly office parks, malls, apartments and single-family homes (villas) dot the landscape.

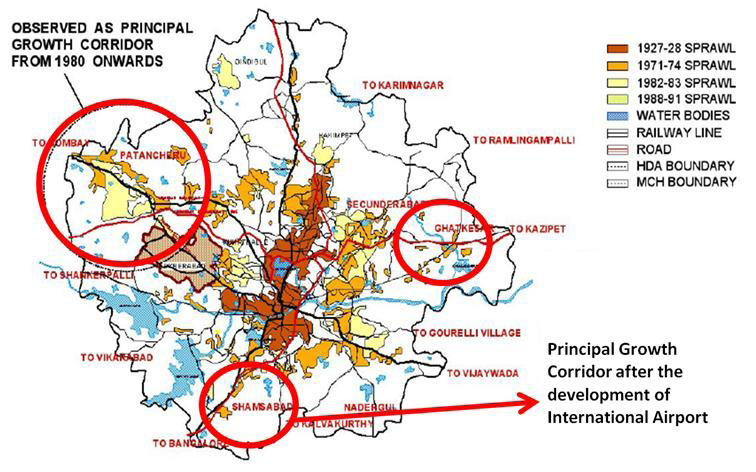

Box 2 explains the process that has led to information-technology driven cities in India.

Therefore, the emerging spatial pattern is an admixture of traditional periurban structures and the suburban and the amalgamated urban space is best described as a periburb (periurban plus suburbs). Presently; the key challenge is to revitalize and guide new growth plus retrofit existing built environment to achieve outcomes valued by citizens using principles of growth management.

The periburbs

These periburban spatial forms are different from the classical low density suburbs located on the periphery of cities (monocentric model) or the emerging nuclei of economic activity (polycentric model), such as “technoburbs” “urban villages” “middle landscape” and “edge cities” As there was little theory or practice available to guide the regional planning process a distinctly Indian approach was developed.

Periburb identification, key concerns and goal determination

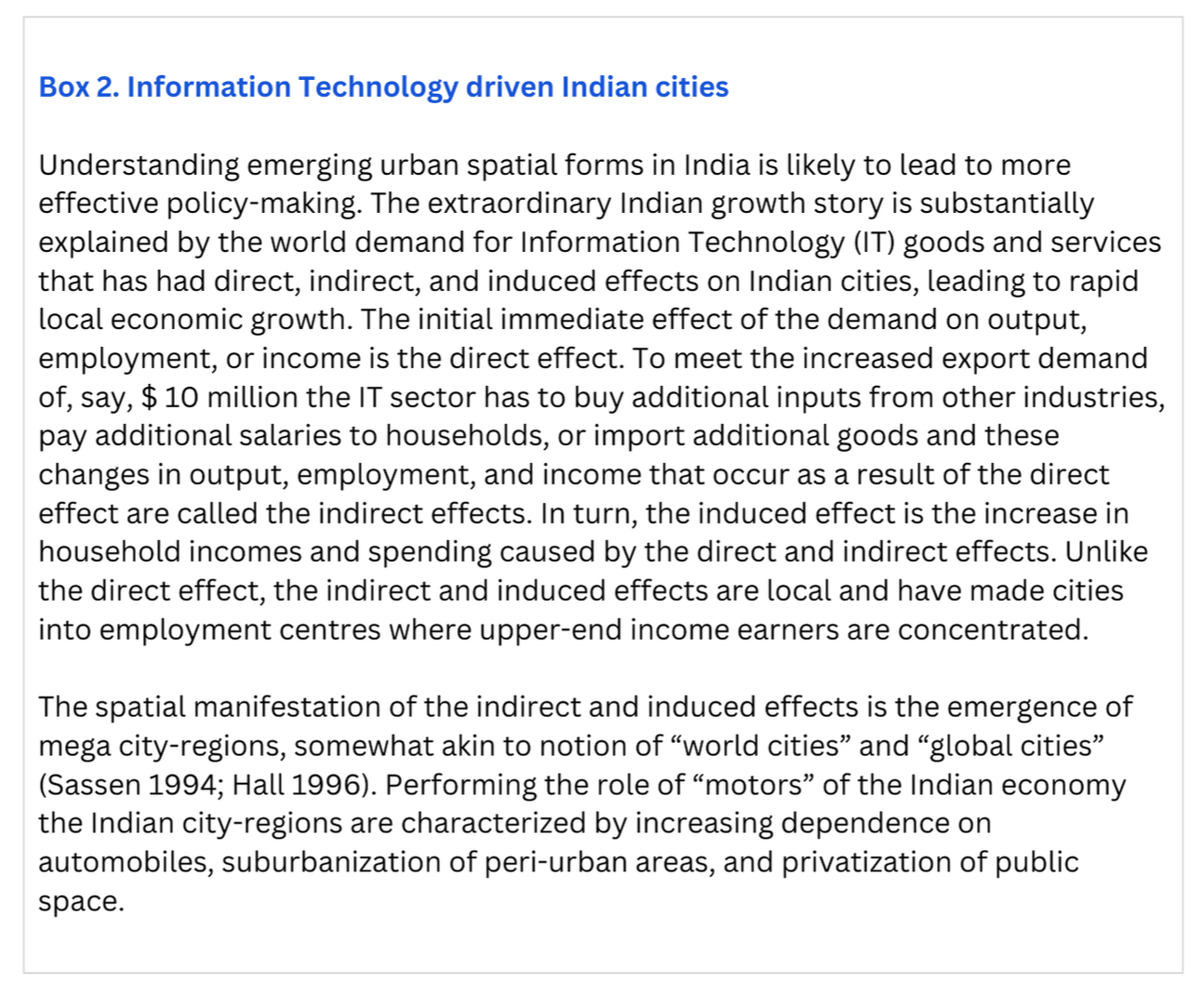

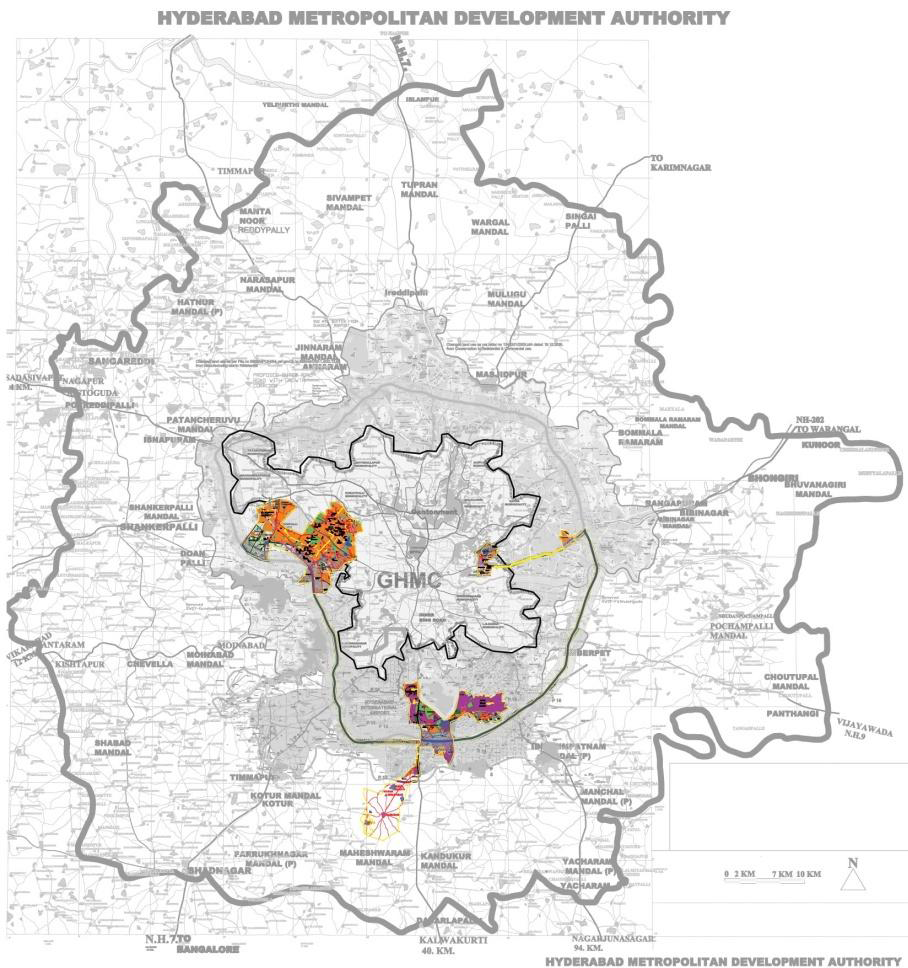

Areas showing potential periburban development were identified by dividing the area into 287 grid-squares and logit regression was applied to determine the probability of development of information technology businesses. Based on the growth directions, three periburbs were identified, given in Figure 1.

Comprehensive plans were prepared to retrofit the brownfield and greenfield areas located in the periburbs. This required identification of the needs of the citizens, especially the ITzens. The underlying idea was based on the notion of creative centres driving city growth. Creative centres are defined by the densities of innovative people rather than those of businesses. Empirical evidence is also available to show that cities promote learning and there is a connection between skills availability and productivity.

Develop the overriding goal: morph them into creative centres, which would be the drivers of the version 2.0 of the Hyderabad growth machine. The assumption was that ITzens have different utility functions, as compared to the “organizational man” of the industrial economy. These were, then, used to determine the goals.

Stakeholder goals: reduce travel times by taking work to the ITzens, promote active living by developing parks within walking distances, create proper infrastructure (e.g., roads, water supply, drainage, rail, metro and solid waste management), promote green cities by reducing carbon footprints and connect to the past by preserving heritage areas.

To achieve the goals, plans were prepared at multiple levels: from the periburb to the neighbourhood scale.

Ward committees and area sabhas were actively involved in the plan preparation at the neighbourhood level. Box 3 gives the key concerns and goals identified by the stakeholders.

Figure 1. Three suburbs of Hyderabad based on growth directions. Source: ITIR document, GoAP

Key elements of the plan

Based on the articulated goals, gaps in the built environment were assessed for the three interconnected periburbs, given in Figure 2. The estimated cost (2010) was as follows:

Internal infrastructure Rs. 13,093 crores.

External infrastructure Rs. 2,189 crores.

Expected benefits during the next 20 years were,

Investments - nearly Rs. 219,440 crores.

Revenues - ~Rs. 30,170 crores for Andhra Pradesh.

Job generation – 15 lakhs direct and 53 indirect.

Governance

A distinct governance structure was also planned. An authority, called the Information Technology Investment Region Development Authority (ITIRDA) was to be established under the Andhra Pradesh Urban Areas Development Act, 1975 to implement the comprehensive plan, which included physical planning, also.

New Planning Ideas

Broadly, the expectation from the ITIRDA were to develop neighborhood plans using postmodern planning ideas, such as principles of New Urbanism principles, neo-traditional development, transit-oriented development (TOD), public-private partnership frameworks and smart growth guidelines because the existing built environment of periburban areas consisted of a mix of conventional (e.g., larger houses in self-contained gated communities, use automobile more often and privatization of public space) and contextual (e.g., markets located at walkable distances, smaller lots clustered together, houses close to lot lines, neighborliness, and greater functional, socio-economic and life-cycle integration).

For example, building stronger and greater number of corner stores was likely to lead to greater retail development that was also well connected to the rest of the neighbourhood. The plan was to construct neighborhoods that were connected to one another by relying on grid roads, rather than collector roads, building houses close to the lot line so that people can easily interact with individuals walking on the footpaths and designing narrower streets to slow traffic.

Specifically, the neighbourhood plan had to look at the built form (e.g., footprints of all structures), land use patterns (e.g., location and density of retail, office spaces), public open space (e.g., parks, plazas), street design (e.g., circulation systems) and pedestrian access (e.g., one-quarter mile access from shops).

Figure 2. Three periburbs connected through corridor. Source: ITIR document, GoAP

Earlier, walkability and opportunities for biking were identified as key goals by the stakeholders. The goal of increasing walkability was planned to be achieved by creating pedestrian sheds, where all elements of a neighbourhood are located within a five-minute walk. Box 4 gives the strategies being followed to make biking more popular. Pedestrian sheds require smaller lot sizes, clustered together and an extension is TOD surrounding a transit stop. In TOD transport is subordinated to development and the strategy is to create mixed-use development around transit stops, so that offices and shops are within walking distance of commuters.

Zoning

The ITIRDA was also expected to design contextual and situated zoning regulations. Ordinarily, four types of zoning codes are followed: Euclidean, form-based, performance, and hybrid. Euclidean zoning can protect neighbourhoods by keeping out incompatible uses; however, stifles mixed use developments and contributes to sprawl by forcing uses apart and limiting density.

On the other hand, form-based regulations promote mixed-use development and pedestrian mobility, but often ignore natural resource issues or favour design over the environment. In Indian cities, we require development codes that directly address sustainability issues like energy conservation and production, climate change, food security, and health and an eclectic mix of Euclidean, form-based, performance, hybrid codes are most likely to achieve sustainability objectives.

The plan for the three periburbs was approved by the Central Government in September 2013.