The Importance of Learning How to Say “No”

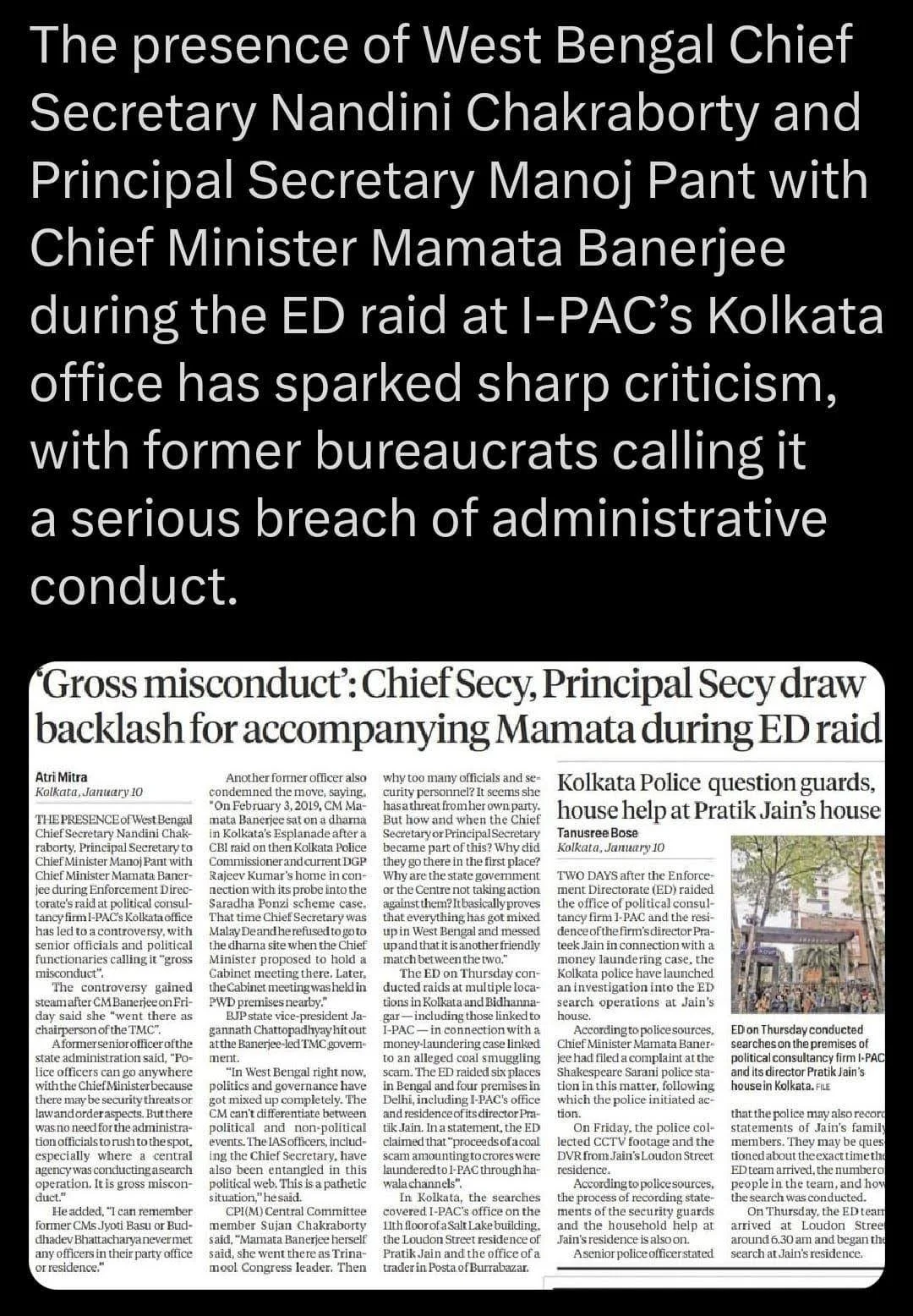

Based on two influential frameworks we can gain deeper insights into events like this:

Stanley Milgram’s Obedience Experiments

Electricity shocks were administered based on instructions of an authority figure. Around 65% of participants administered what they believed were potentially lethal electric shocks to another person when instructed. They showed distress, hesitation, and moral conflict, yet continued.

Hannah Arendt’s concept of the “Banality of Evil”

While observing the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi bureaucrat responsible for organizing mass deportations, she found that Eichmann was not sadistic or fanatical. He was disturbingly ordinary, focused on rules, efficiency, and career advancement. Her conclusion was that evil arises not from monstrous intent, but from thoughtlessness. People engage in this sort of behavior when they:

Stop thinking critically

Treat actions as routine administrative tasks

Prioritize obedience, conformity, and procedural correctness over moral judgment

This was followed by her famous warning: most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

Synthesizing these two approaches tells us why people comply with authority.

Authority provides moral cover - Orders legitimize actions that individuals would otherwise reject.

Rules replace judgment - Procedural correctness substitutes for ethical reasoning.

Distance from consequences reduces empathy - Harm is abstract, indirect, or delayed.

Social and career pressures reward obedience - Compliance is safe; dissent is costly.

Thinking is suspended in favor of efficiency - Moral reflection is seen as disruptive or unnecessary.

Is the solution a defiance of everything? No. For then no organization will be able to operate.

What is required is to learn where to say “Yes” and where to say “No” and, more importantly, how to say No. Some ways of acquiring this skill are described below:

First, develop a deep understanding of reality to judge whether to say yes or no. This requires generating all choices and listing out their consequences. Remember, that you will face anxiety if you reject another person’s suggestion because saying no gives them the signal that they are untrustworthy.

Second, learn and practice the skill of saying no. Start practicing small: telling your barber to stop when they tell you to trust them with a new cut. These small-stakes situations help to build up this skill.

Practicing in daily life will enable you to anticipate the consequences of decision situations and visualize them. It prepares you to face the moment of crisis when you really wish you had done the right thing or said the right thing. In the words of a Greek poet,

“Under duress we don’t rise to the level of our expectations; we fall to the level of our training.”

Third, the manner of saying no is crucial: it need not be loud, bold, and aggressive. There is no need to conflate saying no with defiance and become disruptive or harmful to others. Or, to feel morally superior to others just because they are not saying No. It is equally important to realize that the majority are conditioned from a young age to be compliant and don’t know how to say No, even if they want to.

Over time and with practice, this leads to the development of a mindset (not a personality trait). You act according to your values, especially when there is pressure to do otherwise. Through this, you move from something negative, rare, and risky to something positive and meaningful.